Domain squatting happens when someone registers a domain name with bad intentions – either to block the rightful owner or to make money off someone else’s brand .

It’s a common problem in the digital world that affects businesses and individuals alike.

But what exactly is it?

Domain squatting is the practice of registering, buying, or using domain names with the intent to profit from someone else’s trademark or brand name.

Also known as cybersquatting, this tactic typically involves purchasing domains similar to popular websites or brand names, then trying to sell them at inflated prices or using them to mislead visitors.

The practice creates headaches for legitimate businesses trying to establish their online presence. Companies often find their desired domain names already registered by squatters who demand thousands of dollars for the transfer.

Understanding domain squatting helps businesses protect their online identity and avoid becoming victims of this predatory practice.

About Domain Squatting

Domain Squatting Basics

This practice began in the early days of the internet when many businesses were slow to establish their online presence.

Opportunistic individuals would register domain names of well-known companies or brands, then offer to sell these domains back at inflated prices.

Domain squatting becomes problematic when it violates trademark rights. In many countries, laws like the Anticybersquatting Consumer Protection Act (ACPA) in the United States protect trademark holders from such practices.

Types of Domain Squatting

Several forms of domain squatting exist, each with unique characteristics:

Typosquatting: Registering domains with common misspellings of popular websites. For example, “gooogle.com” instead of “google.com.”

Brand squatting: Directly registering a domain using a known brand name or trademark before the actual company does.

URL hijacking: Using deceptive tactics to direct users to an alternative website, often for malicious purposes.

Name-jacking: Registering domains using the names of celebrities or public figures.

Combination squatting: Using brand names with additional words like “login,” “support,” or “official.”

Domain squatters often monetize these sites through:

- Selling the domain to the trademark owner at a premium

- Displaying ads to profit from mistaken traffic

- Phishing for sensitive user information

Legal Framework and Rights Protection

Laws protect trademark owners from domain squatting.

Several legal mechanisms exist to help businesses recover domain names that infringe on their intellectual property rights.

a) Trademark Law and Domain Names

Trademark law serves as the foundation for combating domain squatting.

When someone registers a domain name that’s similar to a registered trademark, it can constitute trademark infringement under certain conditions.

Courts evaluate several factors when determining if a domain name violates trademark law:

- Similarity to the existing trademark

- Intent behind the registration

- Actual commercial use of the domain

- Potential consumer confusion

Trademark owners must prove the domain was registered in bad faith and that the registrant has no legitimate interest in the name.

International jurisdictions handle these cases differently, but most recognize basic trademark protections for established brands.

First-time registration typically doesn’t automatically grant trademark rights to domain names. The rights develop through actual commercial use and brand recognition.

b) Anti-Cybersquatting Consumer Protection Act (ACPA)

The ACPA passed in 1999 specifically addresses domain squatting in the United States.

This law allows trademark owners to sue domain squatters in federal court.

Under ACPA, plaintiffs can seek:

- Transfer of the domain name

- Statutory damages (up to $100,000 per domain)

- Attorneys’ fees in exceptional cases

To win an ACPA case, the trademark owner must prove:

- They own a valid trademark

- The domain name is identical or confusingly similar

- The registrant acted in bad faith

The law outlines specific factors courts consider when determining bad faith, including offers to sell the domain for profit and intent to divert consumers.

ACPA applies even if the domain was registered before the trademark existed if bad faith can be proven.

c) Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP)

The UDRP provides an alternative to court litigation. Created by the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), this arbitration process offers a faster, less expensive option for resolving domain disputes.

To file a UDRP complaint, trademark owners submit their case to approved dispute resolution providers like the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO).

The three key requirements for a successful UDRP claim:

- The domain is identical or confusingly similar to a trademark

- The registrant has no legitimate rights to the domain

- The domain was registered and used in bad faith

The entire process typically takes 2-3 months. If the complainant prevails, the domain is either transferred or canceled.

Unlike court proceedings, UDRP decisions don’t award monetary damages.

However, the process is significantly faster and cheaper than traditional litigation, making it popular for international disputes.

d) The Electronic Communications and Transactions (ECT) Act in South Africa

More directly, the ECT Act facilitates dispute resolution mechanisms that can be leveraged against cybersquatting.

Section 69 of the Act recognizes the establishment of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) processes for domain name disputes.

This led to the adoption of the .za ADR regulations, modeled after the Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy (UDRP) used internationally.

Under these regulations, trademark holders can challenge bad-faith domain registrations—such as those characteristic of cybersquatting—by filing a complaint with an accredited dispute resolution provider, like the South African Institute of Intellectual Property Law (SAIIPL) or Arbitration Foundation of South Africa (AFSA).

Domain Squatting Tactics and Impacts

Domain squatters employ various techniques to profit from others’ brands and trademarks.

These tactics not only damage businesses financially but also create significant security risks for internet users.

I) Common Typos and Phishing

Domain squatters often register domains with common misspellings of popular websites.

For example, “gooogle.com” instead of “google.com” or “amazom.com” instead of “amazon.com.”

This tactic, known as typosquatting, capitalizes on users’ typing errors.

When users accidentally visit these typosquatted domains, they may encounter sites that look identical to the legitimate ones. These fake sites aim to steal login credentials or personal information.

Domain squatters create these lookalike sites with nearly identical layouts, logos, and color schemes.

The subtle URL difference often goes unnoticed by average users.

Statistics show that phishing attempts through typosquatted domains increased by 35% in the past year alone.

Companies like Amazon, PayPal, and banking institutions are frequent targets due to their high user traffic and sensitive data handling.

II) Malware and Security Threats

Squatted domains frequently serve as distribution points for malware and other security threats.

When users land on these fraudulent sites, they may unknowingly download malicious software.

This malware can take many forms:

- Keyloggers that record everything typed on a keyboard

- Ransomware that encrypts files and demands payment

- Trojans that create backdoor access to computers

- Spyware that monitors user activity

The security implications extend beyond individual users.

Businesses whose brands are imitated face reputation damage when customers associate the malware with their legitimate services.

Domain squatters often target companies during product launches or marketing campaigns when users might search for new domain names.

This timing maximizes exposure to potential victims.

III) Impact on Brand and Consumers

Domain squatting significantly damages brand reputation.

When consumers encounter poor experiences on squatted domains, they often associate that negative experience with the legitimate brand.

Financial impacts can be substantial. Companies may be forced to purchase their own domain variations at inflated prices, sometimes reaching tens of thousands of dollars for popular brand names.

Consumer trust erodes when identity theft occurs through squatted domains. A 2024 survey found that 68% of consumers would stop doing business with a company if they experienced a security breach related to that company’s web presence.

Legal battles over domain disputes drain resources. Even when companies win these cases, the process typically takes months and requires significant legal expenses.

Small businesses suffer disproportionately as they often lack the resources to monitor for squatted domains or pursue legal remedies when violations occur.

Prevention and Protection Strategies

Protecting your brand from domain squatting requires both proactive registration strategies and legal remedies. Taking early action saves businesses significant time, money, and reputation damage.

Registering and Monitoring Domain Names

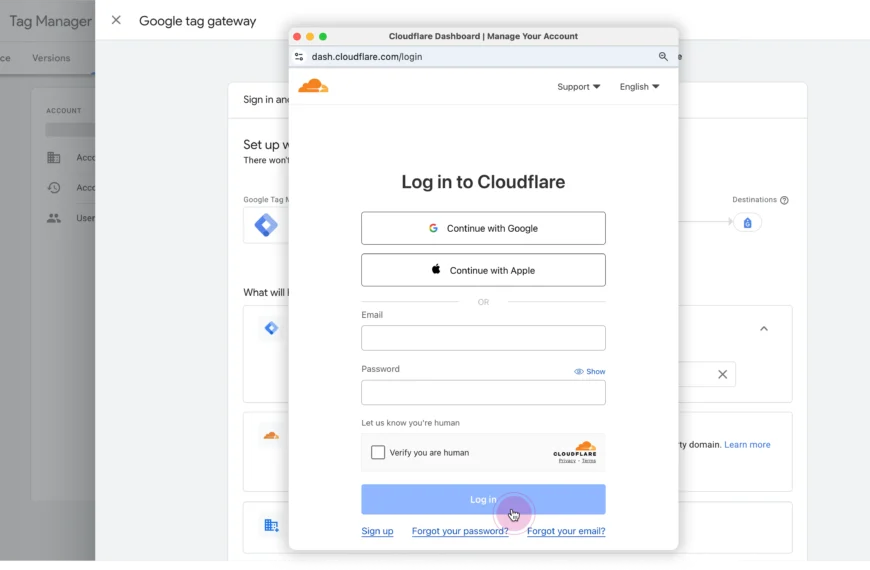

The first line of defense against domain squatting is to register important domains before someone else does.

Businesses should secure their primary domain and common variations including:

- Different top-level domains (.com, .net, .org)

- Common misspellings of the brand name

- Hyphenated versions of the domain

- Country-specific domains for international markets

It’s vital to register domains for at least 2-5 years in advance. Many squatters target recently expired domains of established businesses.

Regular monitoring is equally important.

Companies should use domain monitoring services that alert them when similar domains are registered.

This early warning system helps businesses take quick action against potential squatters.

Consider setting up automatic renewal for all important domains to prevent accidental expiration.

Legal Measures for Trademark Holders

Trademark registration provides powerful legal protections against domain squatters.

Companies should register their business names and key product names as trademarks before launching websites.

The Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy (UDRP) offers a streamlined process for trademark holders to recover squatted domains.

To succeed with a UDRP claim, businesses must prove:

- The domain is identical or confusingly similar to their trademark

- The registrant has no legitimate rights to the domain

- The domain was registered and used in bad faith

Legal action under the Anticybersquatting Consumer Protection Act (ACPA) is another option for U.S. trademark holders. This law allows for:

- Statutory damages up to $100,000 per domain

- Transfer of the disputed domain to the trademark owner

- Attorney’s fees in some cases

Sending a cease and desist letter is often an effective first step before formal legal proceedings.

Responding to Domain Squatting

When faced with domain squatting, individuals and businesses have several effective options to reclaim their domain names.

These approaches involve legal procedures and specialized arbitration processes designed to resolve trademark disputes in the digital space.

Initiating Legal Action

Legal action offers a powerful remedy against domain squatting.

Trademark owners can file lawsuits under the Anticybersquatting Consumer Protection Act (ACPA) in the United States or similar laws in other countries.

These laws allow trademark holders to seek damages ranging from $1,000 to $100,000 per domain name. Courts can also order the transfer of the domain to the rightful trademark owner.

Before filing a lawsuit, sending a cease and desist letter is recommended. This formal document demands the squatter stop using the domain and transfer ownership immediately.

Key requirements for legal action:

- Valid trademark rights

- Proof the domain was registered in bad faith

- Evidence of consumer confusion or dilution of the trademark

Legal action typically costs more than arbitration but may be necessary for complex cases or when substantial damages have occurred.

World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Arbitration

WIPO arbitration provides a faster, less expensive alternative to court proceedings.

This process operates under the Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP), which applies to most domain extensions.

The UDRP process begins by filing a complaint with an approved dispute resolution provider like WIPO.

The entire process typically takes 2-3 months and costs approximately $1,500-$5,000 depending on the number of domains and panelists involved.

To succeed with a UDRP complaint, the complainant must prove:

- The domain is identical or confusingly similar to their trademark

- The registrant has no legitimate rights to the domain

- The domain was registered and used in bad faith

If successful, the domain registration will be cancelled or transferred to the complainant. The process doesn’t award monetary damages but provides an efficient path to reclaim domain names from squatters acting in bad faith.

Domain SearchInstantly check and register your preferred domain name

Domain SearchInstantly check and register your preferred domain name Web Hosting

Web Hosting cPanel HostingHosting powered by cPanel (Most user friendly)

cPanel HostingHosting powered by cPanel (Most user friendly) KE Domains

KE Domains Reseller HostingStart your own hosting business without tech hustles

Reseller HostingStart your own hosting business without tech hustles Windows HostingOptimized for Windows-based applications and sites.

Windows HostingOptimized for Windows-based applications and sites. Free Domain

Free Domain Affiliate ProgramEarn commissions by referring customers to our platforms

Affiliate ProgramEarn commissions by referring customers to our platforms Free HostingTest our SSD Hosting for free, for life (1GB storage)

Free HostingTest our SSD Hosting for free, for life (1GB storage) Domain TransferMove your domain to us with zero downtime and full control

Domain TransferMove your domain to us with zero downtime and full control All DomainsBrowse and register domain extensions from around the world

All DomainsBrowse and register domain extensions from around the world .Com Domain

.Com Domain WhoisLook up domain ownership, expiry dates, and registrar information

WhoisLook up domain ownership, expiry dates, and registrar information VPS Hosting

VPS Hosting Managed VPSNon techy? Opt for fully managed VPS server

Managed VPSNon techy? Opt for fully managed VPS server Dedicated ServersEnjoy unmatched power and control with your own physical server.

Dedicated ServersEnjoy unmatched power and control with your own physical server. SupportOur support guides cover everything you need to know about our services

SupportOur support guides cover everything you need to know about our services